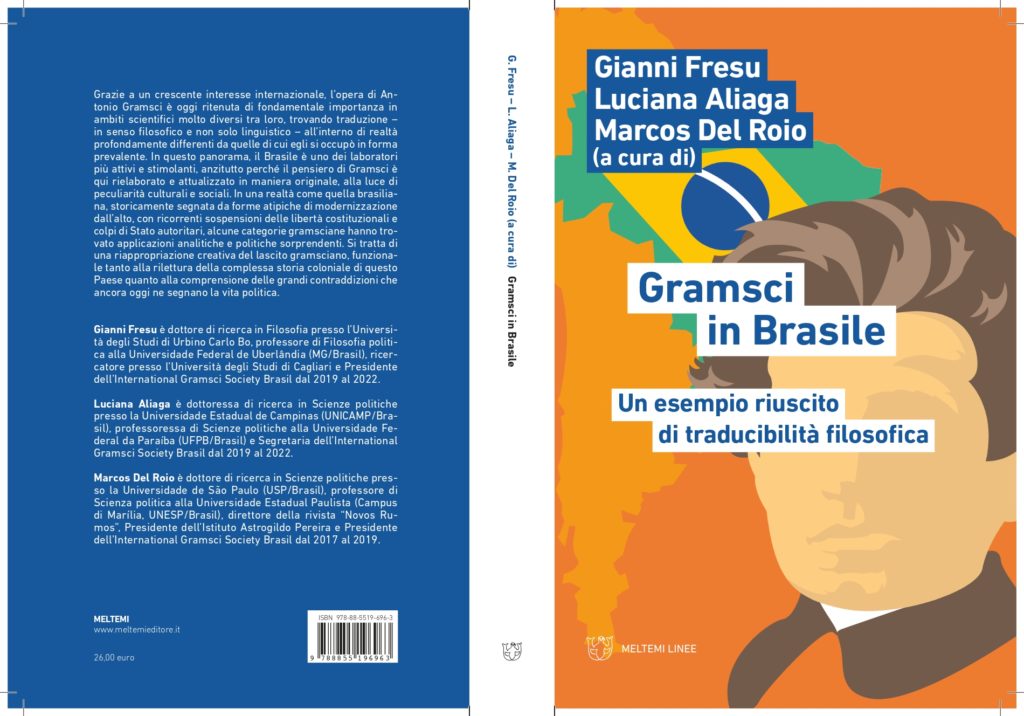

Gramsci in Brasile. Un esempio riuscito di traducibilità filosofica, (a cura di) Gianni Fresu, Luciano Aliaga, Marcos Del Roio, Meltemi, Milano, 2022, ISBN, 9788855196963, (366 pagine)

Grazie a un crescente interesse internazionale, l’opera di Antonio Gramsci è oggi ritenuta di fondamentale importanza per ambiti scientifici molto diversi tra loro, trovando traduzione (in senso filosofico e non solo linguistico) all’interno di realtà profondamente diverse da quelle di cui egli si occupò in forma prevalente. In questo panorama il Brasile è uno dei laboratori più attivi e stimolanti, anzitutto perché il suo pensiero è qui rielaborato e attualizzato in maniera originale alla luce delle peculiarità culturali e sociali nazionali. In una realtà come quella brasiliana, storicamente segnata da forme atipiche di modernizzazione dall’alto, con ricorrenti sospensioni delle libertà costituzionali e colpi di Stato autoritari, alcune categorie gramsciane hanno trovato applicazioni analitiche e politiche sorprendenti. Una riappropriazione creativa del lascito gramsciano, funzionale tanto alla rilettura della complessa storia coloniale di questo Paese quanto alla comprensione delle grandi contraddizioni che ancora oggi ne segnano la vita politica.